This blog is jointly authored by Victoria Crooks and Alex Ford. Check out http://www.andallthat.co.uk/ to read more blogs from Alex.

Matthew is a fab beginning teacher. He is highly professional, and his subject knowledge is second to none. Simon, his mentor, is delighted by the deeply informed historical discussions they are having during mentor meetings about a range of different elements in the curriculum. Matthew is thinking about pupils and making efforts to model and scaffold. Lessons are well paced; he has his questioning down and is consistent around checking for understanding.

However, while Matthew is surprisingly excellent at identifying what he wants to teach his pupils, and why this is important for the development of their historical understanding, all too often his lessons are falling flat. Lesson tasks just don’t really seem to fit the historical ambitions he outlines in the learning objectives. Something feels off about the pitch of lessons, they can feel simultaneously too hard and too easy or, quite simply, just a bit ‘meh’. Students are struggling, despite the attention Matthew gives to trying to meet their needs and despite his own grasp of the rationale.

Simon feels he has a way in to talking about the connection between lesson activities and the rationale of the lesson – he’s seen this before with a previous mentee, Seb. He is convinced that some of Matthew’s problems are due to having not connected his WHAT and WHY to examples of different types of activities (the HOW). The pitching issue is a bit trickier, however. Even Simon isn’t sure what he means by the ‘Think about the pitch of your lesson’ target he set Matthew in this week’s mentor meeting. He certainly doesn’t know where to begin with creating some action steps…

The elusive concept of ‘lesson pitch’

Mentors often find themselves grappling with the elusive concept of ‘pitching’—how complex or abstract a lesson should be for pupil understanding. Beginning teachers are told their lessons were “too simple” or “too abstract,” but the diagnosis as to why the pitching is off is often lacking or reduced to a discussion of sequencing even though it is about more than this.

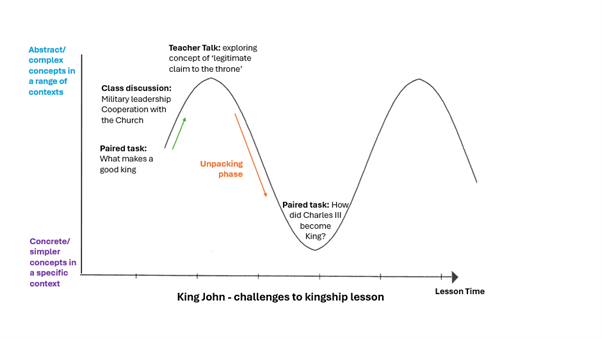

Legitimation Code Theory (LCT) provides a way in to articulating these challenges of pitch. In a nutshell, LCT research suggests that the most effective teachers are constantly changing the complexity of the concepts they are covering during a lesson. This movement from complex and abstract concepts to simple and concrete ones is known as a ‘semantic wave’. Crucially, effective teachers know when they need to move students up or down a semantic wave – adding complexity or breaking things down. Beginning teachers can use the concepts of ‘semantic waves’ when observing expert teachers to identify how they move between the complex and abstract and the simple and concrete, as well as identifying why the teacher might have made this choice.

What are semantic waves?

When experienced teachers and mentors talk about a lesson that is well-pitched, they usually mean a lesson that does not stay at one level of complexity or context. Instead, well-pitched lessons move in continuing pattern between the more complex and abstract and the simpler and concrete (Maton, 2013). The wave is the teacher’s deliberate navigation between abstract theory and concrete examples, and it is this pattern that is important for pupils if they are to build and consolidate their knowledge.

For beginning teachers struggling with pitch, conceptualising their lesson planning as a series of waves that connects concrete and abstract knowledge in quick succession to support pupil learning can make all the difference.

Beginning teachers can focus on the pitch of their lessons if they understand how expert teachers are able to move from high to low points on semantic waves at key points in the lesson.

Let’s take an example. A teacher looking at rebellions against King John might begin by exploring the qualities of good kingship. This might lead to some discussion about moderately complex but fairly abstract concepts like military leadership or the ability to cooperate with the Church. However, it might also include more complex concepts like having a legitimate claim to the throne. This input might come from teacher talk, a worksheet or video for example.

For many new teachers, the aim might be to get pupils to identify all the key qualities of being a good medieval king and noting them down. A more experienced teacher however might recognise that a concept like ‘legitimacy’ requires simplification for pupils to grasp it. They might for example bring up the concept, then immediately move to getting pupils to think about how the current King was enabled to ascend to the throne. In this case pupils are moved from the abstract concept of legitimacy to the concrete example of a single king’s claim. This moves the content much lower on the semantic wave, aiming to give an access point for pupils.

From here an experienced teacher might then explore how legitimacy today is similar and different to the legitimacy of a medieval monarch like John. Here the teacher begins to move pupils back up from the concrete example to something which is more abstract once again.

For a trainee teacher, this kind of move might go unnoticed. Even for an experienced teacher, this decision to simplify and break something down is often described in terms of ‘gut feeling’ rather than in terms of ‘semantic waves’. However, if a trainee is explicitly looking for when the semantic wave of a lesson changes, they can have more useful discussion about why an experienced colleague chose to break something down or build something up at a particular point.

How can mentors use semantic waves with beginning teachers?

LCT, through the exploration of a lesson’s semantic profile, can provide a tool for analysing teaching practice by providing a common language for mentors and mentees to discuss the structure of the knowledge being taught. Ultimately it can help the beginning teacher to understand the impact of their pedagogical choices on pupil learning.

When observing a lesson, rather than completing a traditional observation proforma, mentors can instead plot an annotated semantic wave, focusing on how the lesson pitch varied at different critical moments. This may include time stamps with notes about what was happening at that point in the lesson with brief observations of how this was impacting pupil learning. Through plotting the semantic wave, mentors may notice some of the following patterns:

| Observation | What you see in the semantic wave |

| The beginning teacher successfully unpacked the complex concept into examples but failed to repack it. The wave never strengthened back to the abstract level, so pupils were unable to independently apply the concept to new situations. | Down Escalator |

| The beginning teacher stayed at a highly abstract and complex level without providing concrete examples. The wave started too high, leaving the knowledge opaque and non-transferable | Flatline (High) |

| The beginning teacher only worked with simple, context-specific examples and failed to condense them into a powerful theoretical concept. The wave didn’t peak. | Flatline (Low) |

The post lesson conversation between the mentor and mentee can explore the relationship between the sequencing of tasks and the movement from abstract to concrete knowledge that helps pupils to make meaningful connections and results in changes in their knowledge and understanding.

Beginning teachers may also find value in undertaking semantic wave observations of more experienced colleagues, thinking about how they use semantic density and semantic gravity to ensure lessons are appropriately pitched.

Surfing the Semantic Wave

Talking about the pitch of lessons is tricky. It is hard to conceptualise and discuss. LCT provides an opportunity for teachers to render visible this classroom challenge and to begin to find a way forward. It may be time to add ‘surfing the semantic wave’ to your observation repertoire. For Matthew, it could really help unlock his thinking around the connection between teaching and learning in his classroom.

References:

Legitimation Code Theory Website, https://legitimationcodetheory.com/ [accessed 21/11/2025]

Macnaught, L., Maton, K., Martin, J. R., & Matruglio, E. (2013). Jointly constructing semantic waves: Implications for teacher training. Linguistics and Education, 24(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2012.11.008

Maton, K. (2013). Making semantic waves: A key to cumulative knowledge-building. Linguistics and Education, 24(1), 8–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2012.11.005